While some immune cells aim to fight cancer, others hold them in check

Many cancer patients generate immune cells capable of specifically attacking their tumors, but the cells rarely do, in fact, target a patient’s cancer. What prevents these potentially helpful cells from taking action? And is there anything that might be done to unleash them?

The attack cells – known as cytolytic T cells – are prevented from acting by a second set of immune cells called regulatory T cells, according to a new study from investigators at The Wistar Institute. The research also shows that the regulatory T cells communicate their message of restraint to the cytolytic T cells at a distance, via a messenger chemical called TGF-beta. A report on the study appears in the September 15 issue of Cancer Research.

Previous work has focused on ways to stimulate the cytolytic T cells to act, but the new study suggests that other approaches to bringing them into the battle against cancer might be more effective. For example, a drug that inactivates the regulatory T cells or that blocks the TGF-beta chemical message they send might free the cytolytic T cells to attack a patient’s tumor.

“We’ve known for some time that cancer patients can generate T cells able to attack their tumors,” says immunologist Dorothee Herlyn, D.V.M., D.Sc., a professor at The Wistar Institute and senior author on Cancer Research study. “What we discovered in this study is that those patients also produce negatively regulating cells at the same time that keep the attacking T cells in check. The existence of these regulatory cells may help explain how tumors are able to evade the immune system. They also represent a new starting point for thinking about novel anti-cancer treatments.”

The current study evolved somewhat by chance. Using cells from a human colorectal cancer patient, Herlyn’s laboratory team was working to identify T cells with cancer-fighting capabilities and isolate them from other types of immune cells. At one point, one of her coworkers suggested combining different groups of isolated cell types to look for interactions between them.

“We put these two different types of immune cell together, one of which killed cancer cells in culture, the other of which did not,” Herlyn recalls. “When we did, we were stunned to see that the one that had previously killed cancer cells no longer did so.”

Adequately explaining the mechanisms underlying that observation required several years of additional study, she says.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.wistar.upenn.edu/All latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

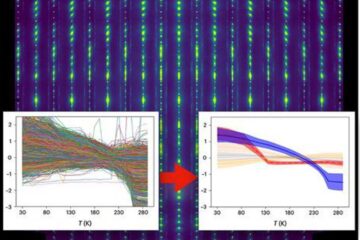

Machine learning algorithm reveals long-theorized glass phase in crystal

Scientists have found evidence of an elusive, glassy phase of matter that emerges when a crystal’s perfect internal pattern is disrupted. X-ray technology and machine learning converge to shed light…

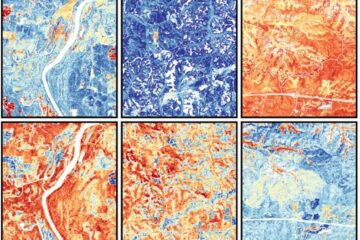

Mapping plant functional diversity from space

HKU ecologists revolutionize ecosystem monitoring with novel field-satellite integration. An international team of researchers, led by Professor Jin WU from the School of Biological Sciences at The University of Hong…

Inverters with constant full load capability

…enable an increase in the performance of electric drives. Overheating components significantly limit the performance of drivetrains in electric vehicles. Inverters in particular are subject to a high thermal load,…