Early Warning System Provides Four-Month Forecast of Malaria Epidemics in Northwest India

Colder-than-normal July sea surface temperatures in the tropical South Atlantic are linked to both increased monsoon rainfall and malaria epidemics in the arid and semi-arid regions of northwest India, including the vast Thar desert, according to Mercedes Pascual and her colleagues, who summarize their findings in a paper to be published online March 3 in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Previous efforts to forecast malaria outbreaks in northwest India have focused largely on monsoon-season rainfall totals as a predictor of the availability of breeding sites for the Anopheles mosquitoes that transmit the disease. That approach provides about a month of lead time before outbreaks occur.

The new forecasting tool should improve public health in the region by increasing warning time, thereby informing decisions about treatment preparedness and other disease-prevention strategies, said Pascual, the Rosemary Grant Collegiate Professor of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. Planning for indoor insecticide spraying, one widely used control measure, could benefit from the additional lead time, for example.

“The climate link we have uncovered can be used as an indicator of malaria risk,” Pascual said. “On the practical side, we hope these findings can be used as part of an early warning system.”

After being nearly eradicated in India, malaria re-emerged there in the 1970s. An estimated 9 million malaria cases occur in India annually.

Malaria in its epidemic form occurs primarily on the margins of the geographical distribution of the disease, in places like arid northwest India where environmental conditions are only episodically suitable for sustaining Anopheles mosquitoes.

Motivated by the desire for more accurate prediction of malaria risk at longer lead times, Pascual and her colleagues analyzed epidemiological records of malaria incidence in northwest India and used statistical and computer climate models to test potential links between sea surface temperatures, monsoon rains in northwest India, and malaria epidemics there.

They found that most malaria epidemics in northwest India, which peak in October or November, occur when rainfall in the preceding summer monsoon season equals or exceeds a rainfall threshold presumably required to support the growth of Anopheles mosquitoes.

The researchers looked for a correlation between global sea-surface temperatures and epidemic malaria in northwest India. They identified a broad region in the tropical South Atlantic, west of Africa, where cooler-than-normal sea-surface temperatures are significantly associated with increases in both monsoon rainfall and malaria incidence in northwest India.

July sea-surface temperatures in the tropical South Atlantic proved to be remarkably accurate at predicting malaria outbreaks in northwest India during the following fall. In a retrospective analysis of malaria epidemics in the region between 1985 and 2006, the researchers found that July sea surface temperatures correctly anticipated nine out of 11 epidemic years and 12 out of 15 non-epidemic years.

“For this region of India and for this window of time in recent decades, the tropical South Atlantic appears to play a dominant role on rainfall and, through rainfall, on malaria,” Pascual said.

Malaria is caused by the Plasmodium parasite, which is transmitted via the bites of infected mosquitoes. In the human body, the parasites multiply in the liver and then infect red blood cells.

Pascual's co-authors on the Nature Climate Change paper are B.A. Cash of the Center for Ocean-Land-Atmosphere Studies, X. Rodó of the Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats and the Institut Català de Ciències del Clima in Spain, J. Ballester of the Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats in Spain, M.J. Bouma of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, A. Baeza of the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and R. Dhiman of the National Institute of Malaria Research in New Delhi, India.

The work was supported by the National Institute of Malaria Research in New Delhi, U-M's Graham Sustainability Institute, and by grants from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the National Science Foundation and NASA. The National Center for Atmospheric Research provided high-performance computing support.

Mercedes Pascual: www.lsa.umich.edu/eeb/directory/faculty/pascual

EDITORS: High-res photos available at www.ns.umich.edu/Releases/2013/Feb13/malaria.html

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.umich.eduAll latest news from the category: Health and Medicine

This subject area encompasses research and studies in the field of human medicine.

Among the wide-ranging list of topics covered here are anesthesiology, anatomy, surgery, human genetics, hygiene and environmental medicine, internal medicine, neurology, pharmacology, physiology, urology and dental medicine.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

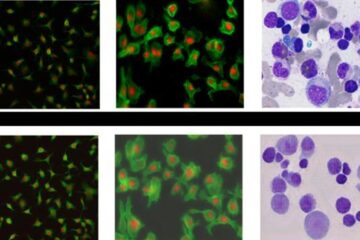

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…