UM Scientists Create Fruit Fly Model to Help Unravel Genetics of Human Diabetes

While sedentary lifestyles and diets high in sugar and fat contribute significantly to the rise in diabetes rates, genetic factors may make some people more vulnerable than others to developing diabetes.

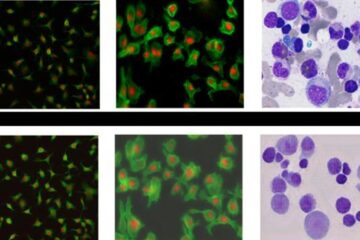

Researchers at the University of Maryland are using the fruit fly, Drosophila Melanogaster, as a model system to unravel what genes and gene pathways are involved in the metabolic changes that lead to insulin resistance and full-blown diabetes in humans. In research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (November 2, 2009), Leslie Pick, an associate professor in the department of entomology, and colleagues describe how they altered genes in fruit flies to model the loss of insulin production, as seen in human Type 1 diabetes.

“These mutant flies show symptoms that look very similar to human diabetes,” explains Dr. Pick. “They have the hallmark characteristic which is elevated blood sugar levels. They are also lethargic and appear to be breaking down their fat tissue to get energy, even while they are eating — a situation in which normal animals would be storing fat, not breaking it down.”

Understanding Type 1 Diabetes

In mammals, insulin is a key hormone required for sugar metabolism. After a meal, blood sugar levels rise. Insulin triggers the uptake of this sugar from circulation to be converted into storage products in tissues such as muscle and fat. In humans, Type 1 diabetes (also called Juvenille Diabetes Mellitus, or early onset diabetes), insulin production fails. As a result, the body is missing the key signal required for uptake of sugar from the circulation. Circulating sugar levels continue to rise, as the body fails to sense the presence of sugar, and instead responds as if it is starving, beginning to break down storage products to produce energy.

Pick and her team, which included University of Maryland researchers Hua Zhang, Jingnan Liu, and Caroline Li, Associate Professor Bahram Momen (biostatistics and environmental science), and former Johns Hopkins University Associate Professor Dr. Ronald Kohanski, used genetic approaches to delete a cluster of five genes encoding insulin-like peptides (Drosophila insulin-like peptides, DILPs) in the Drosophila melanogaster fruit fly. “When we compare the mutants with a normal fly that has been starved, they look the same in that they are both breaking down their fat to get energy,” Pick explains. This mimics a clinical feature of diabetic patients resulting from the fact that nutrients are present but the body cannot utilize them and thus mounts a starvation response, breaking down energy stores to obtain nutrients.

“We can use these genetically manipulated flies as a model to understand defects underlying human diabetes and to identify genes and target points for pharmacological intervention,” suggests Dr. Pick, who is also using flies to study Type 2 diabetes and other syndromes of insulin resistance.

Model organisms have proven enormously valuable for studies of human disease mechanisms because regulatory pathways and physiology are so highly conserved throughout the animal kingdom. The relationship between fly and human genes is so close that human genes, including disease genes, can often be matched against their fly counterparts.

“Way more is shared between flies and humans than we ever would have expected before we started identifying the genes,” says Pick. Using flies as a model system has advantages over studies in other animals, such as mice, because the experiments can be done quickly in thousands of flies and because scientists can combine different mutations much more easily. This could prove valuable in understanding the genesis of Type 2 diabetes in which scientists believe multiple genes play a role.

“When we made the genetic mutation that deleted these genes, we asked would these flies have any symptoms of human diabetes, and it turns out they do,” Pick says. “That tells us that there are some things going on that are very similar. Our hope is that this provides a valuable resource for the scientific community to identify gene targets for diabetes treatment.”

This research was funded primarily by the National Institutes of Health.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.umd.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…