Study Finds New Genes that Cause Baraitser-Winter Syndrome, a Brain Malformation

Scientists from Seattle Children’s Research Institute and the University of Washington, in collaboration with the Genomic Disorders Group Nijmegen in the Netherlands, have identified two new genes that cause Baraitser-Winter syndrome, a rare brain malformation that is characterized by droopy eyelids and intellectual disabilities.

“This new discovery brings the total number of genes identified with this type of brain defect to eight,” said William Dobyns, MD, a geneticist at Seattle Children’s Research Institute. Identification of the additional genes associated with the syndrome make it possible for researchers to learn more about brain development. The study, “De novo mutations in the actin genes ACTB and ACTG1 cause Baraitser-Winter syndrome,” was published online February 26 in Nature Genetics.

The brain defect found in Baraitser-Winter syndrome is a smooth brain malformation or “lissencephaly,” as whole or parts of the surface of the brain appear smooth in scans of patients with the disorder. Previous studies by Dr. Dobyns and other scientists identified six genes that cause the smooth brain malformation, accounting for approximately 80% of affected children. Physicians and researchers worldwide have identified to date approximately 20 individuals with Baraitser-Winter syndrome.

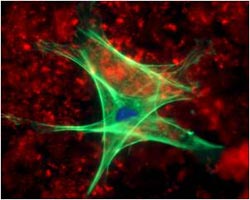

While the condition is rare, Dr. Dobyns said the team’s findings have broad scientific implications. “Actins, or the proteins encoded by the ACTB and ACTG1 genes, are among the most important proteins in the function of individual cells,” he said. “Actins are critical for cell division, cell movement, internal movement of cellular components, cell-to-cell contact, signaling and cell shape,” said Dr. Dobyns, who is also a University of Washington professor of pediatrics. “The defects we found occur in the only two actin genes that are expressed in most cells,” he said. Gene expression is akin to a “menu” for conditions like embryo development or healing from an injury. The correct combination of genes must be expressed at the right time to allow proper development. Abnormal expression of genes can lead to a defect or malformation.

“Birth defects associated with these two genes also seem to be quite severe,” said Dr. Dobyns. “Children and people with these genes have short stature, an atypical facial appearance, birth defects of the eye, and the smooth brain malformation along with moderate mental retardation and epilepsy. Hearing loss occurs and can be progressive,” he said.

Dr. Dobyns is a renowned researcher whose life-long work has been to try to identify the causes of children’s developmental brain disorders such as Baraitser-Winter syndrome. He discovered the first known chromosome abnormality associated with lissencephaly (Miller-Dieker syndrome) while still in training in child neurology at Texas Children’s Hospital in 1983. That research led, 10 years later, to the discovery by Dobyns and others of the first lissencephaly gene known as LIS1.

Dr. Dobyns’ co-authors on this study include: Jean-Baptiste Riviere, PhD, Seattle Children’s Research Institute; Christopher Sullivan, Seattle Children’s Research Institute; Susan Christian, Seattle Children’s Research Institute; Brian O’Roak, PhD, University of Washington; Jay Shendure, MD, PhD, University of Washington; and many other physicians and scientists from North America and Europe.

Additional Resources

“De novo mutations in the actin genes ACTB and ACTG1 cause Baraitser-Winter syndrome”: http://www.nature.com/ng/journal/vaop/ncurrent/full/ng.1091.html

“Baraitser-Winter syndrome” study slideshow: http://www.flickr.com/photos/38997016@N03/sets/72157629446519959/

“Baraitser-Winter syndrome” studies: “Isolation of a Miller-Dieker lissencephaly gene containing G protein beta-subunit-like repeats” http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8355785; “doublecortin, a Brain-Specific Gene Mutated in Human X-Linked Lissencephaly and Double Cortex Syndrome, Encodes a Putative Signaling Protein” http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9489700

About Seattle Children’s Research Institute

At the forefront of pediatric medical research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute is setting new standards in pediatric care and finding new cures for childhood diseases. Internationally recognized scientists and physicians at the research institute are advancing new discoveries in cancer, genetics, immunology, pathology, infectious disease, injury prevention and bioethics. With Seattle Children’s Hospital and Seattle Children’s Hospital Foundation, the research institute brings together the best minds in pediatric research to provide patients with the best care possible. Children’s serves as the primary teaching, clinical and research site for the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Washington School of Medicine, which consistently ranks as one of the best pediatric departments in the country. For more information, visit http://www.seattlechildrens.org/research

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.seattlechildrens.orgAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Superradiant atoms could push the boundaries of how precisely time can be measured

Superradiant atoms can help us measure time more precisely than ever. In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen present a new method for measuring the time interval,…

Ion thermoelectric conversion devices for near room temperature

The electrode sheet of the thermoelectric device consists of ionic hydrogel, which is sandwiched between the electrodes to form, and the Prussian blue on the electrode undergoes a redox reaction…

Zap Energy achieves 37-million-degree temperatures in a compact device

New publication reports record electron temperatures for a small-scale, sheared-flow-stabilized Z-pinch fusion device. In the nine decades since humans first produced fusion reactions, only a few fusion technologies have demonstrated…