Researchers Unveil Molecular Details of How Bacteria Propagate Antibiotic Resistance

Unfortunately, in time, these treatments also can fall prey to the same microbial ability to become drug resistant. Now, a research team at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC) may have found a way to break the cycle that doesn’t demand the deployment of a next-generation medical therapy: preventing “superbugs” from genetically propagating drug resistance.

The team will present their findings at the annual meeting of the American Crystallographic Association (ACA), held July 28 – Aug. 1 in Boston, Mass.

For years, the drug vancomycin has been the last-stand treatment for life-threatening cases of methicilin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA. A powerful antibiotic first isolated in 1953 from soil collected in the jungles of Borneo, vancomycin works by inhibiting formation of the S. aureus cell wall so that it cannot provide structural support and protection. In 2002, however, a strain of S. aureus was isolated from a diabetic kidney dialysis patient. This particular strain would not succumb to vancomycin. This was the first recorded instance in the United States of vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or VRSA, a deadly variant that many now consider one of the most dangerous bacteria in the world.

Former UNC graduate student Jonathan Edwards (now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology), under the guidance of chemistry professor Matthew Redinbo, led the research team that sought a detailed biochemical understanding of the VRSA threat. They focused on a S. aureus plasmid – a circular loop of double-stranded DNA within the Staph cell separate from the genome – called plW1043 that codes for drug resistance and can be transferred via conjugation (“mating” that involves genetic material passing through a tube from a donor bacterium to a recipient).

Before the plasmid gene for drug resistance can be passed, it must be processed for the transfer. This occurs when a protein called the Nicking Enzyme of Staphylococci, or NES, binds with its active area, known as the relaxase region, to the donor cell plasmid. NES then cuts, or “nicks,” one strand of the double helix so that it separates into two single strands of DNA. One moves into the recipient cell while the other remains with the donor. After the two strands are replicated, NES reforms the plasmid in both cells, creating two drug-resistant Staph cells that are ready to spread their misery further.

Using X-ray crystallography, Edwards, Redinbo, and their colleagues defined the structure of both ends of the VRSA NES protein, the N-terminus where the relaxase region resides and the molecule’s opposite end known as the C-terminus. They noticed that the N-terminus structure included a region with two distinct protein loops. Suspecting that this area might play a critical role in the VRSA plasmid transfer process, the researchers cut out the loops. This kept the NES relaxase region from clamping onto or staying bound to the plasmid DNA.

Biochemical assays showed that the function of the loops was indeed to keep the relaxase region attached to the plasmid until nicking occurred. This took place, the researchers learned, in the minor groove of a specific DNA sequence on the plasmid.

“We realized that a compound that could block this groove, prevent the NES loops from attaching and inhibit the cleaving of the plasmid DNA into single strands could potentially stop conjugal transfer of drug resistance altogether,” Edwards says.

To test their theory in the laboratory, the researchers used a Hoechst compound – a blue fluorescent dye used to stain DNA – that could bind to the minor groove. As predicted, blocking the grove prevented nicking of the plasmid DNA sequence.

Redinbo says that this “proof of concept” experiment suggests that the same inhibition might be possible in vivo. “Perhaps by targeting the DNA minor groove, we might make antibiotics more effective against VRSA and other drug-resistant bacteria,” he says.

This news release was prepared for the American Crystallographic Association (ACA) by the American Institute of Physics (AIP).

MORE INFORMATION ABOUT THE 2012 ACA MEETINGThe ACA is the largest professional society for crystallography in the United States, and this is its main meeting. All scientific sessions, workshops, poster sessions, and events will be held at the Westin Waterfront Hotel in Boston, Mass.

USEFUL LINKS:

Main meeting website: http://www.amercrystalassn.org/2012-meeting-homepage

Meeting program: http://www.amercrystalassn.org/2012-tentative-program

Meeting abstracts: http://www.amercrystalassn.org/app/sessions

Exhibits: http://www.amercrystalassn.org/2012-exhibits

ABOUT ACA

The American Crystallographic Association (ACA) was founded in 1949 through a merger of the American Society for X-Ray and Electron Diffraction (ASXRED) and the Crystallographic Society of America (CSA). The objective of the ACA is to promote interactions among scientists who study the structure of matter at atomic (or near atomic) resolution. These interactions will advance experimental and computational aspects of crystallography and diffraction. They will also promote the study of the arrangements of atoms and molecules in matter and the nature of the forces that both control and result from them.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

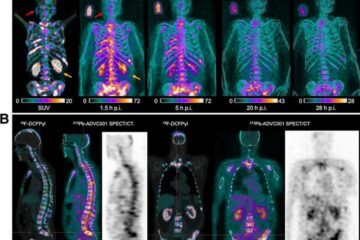

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…