One gene 90 percent responsible for making common parasite dangerous

The finding, reported in this week's issue of Science by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and elsewhere, should make it easier to identify the parasite's most virulent strains and treat them.

The results suggest that when a more harmful strain of T. gondii appears, approximately 90 percent of the time it will have a different form of the virulence gene than that found in the more benign strains of the parasite.

Infection with T. gondii, or toxoplasmosis, is perhaps most familiar to the general public from the widespread recommendation that pregnant women avoid changing cat litter. Cats are commonly infected with the parasite, as are some livestock and wildlife. T. gondii's most infamous relatives are the parasites that cause malaria.

Epidemiologists estimate that as many as one in every four humans is infected with T. gondii. Infections are typically asymptomatic, only causing serious disease in patients with weakened immune systems. In some rare cases, though, infection in patients with healthy immune systems leads to serious eye or central nervous system disease, or congenital defects or death in the fetuses of pregnant women. Historically, scientists have found strains of T. gondii difficult to tell apart, heightening the mystery of occasional serious infections in healthy people.

“Clinically it may be helpful to be able to test the form of the parasite causing the infection to determine if a case requires aggressive management and treatment or is unlikely to be a cause of serious disease,” says senior author L. David Sibley, Ph.D. professor of molecular microbiology. “This finding will advance us toward that goal.”

ROP18, the T. gondii virulence gene identified by researchers, makes a protein that belongs to a class of signaling factors known as kinases that are ubiquitous in human biology.

“Kinases are active in cancers and autoimmune disorders, so pharmaceutical companies already have libraries of inhibitors they've developed to block the activity of these proteins,” Sibley says. “Some patients can't tolerate the antibiotics we currently use to treat T. gondii infection, so in future studies we will want to screen these inhibitor libraries to see if one can selectively block ROP18 and serve as a more effective treatment.”

The Institute for Genomic Research, in collaboration with the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, completed sequencing of the T. gondii genome in 2004. Three separate postdoctoral fellows (the co-first authors of the paper) then used three different post-genomic techniques to search the genome for potential virulence factors.

“All the approaches we used eventually pointed emphatically to a single gene, ROP18,” Sibley notes. “The readings were just off the scale.”

A survey of isolates from T. gondii strains from around the world found ROP18 and its effects on virulence to be widespread.

“The protein made by the ROP18 gene has an interesting and predictable function,” says Sibley. “The parasite uses it to get a host cell 'drunk,' secreting the protein into the host after infection.”

Inside the host cell, ROP18 presumably disrupts some important signaling process, altering the intracellular environment in a way that favors the parasite's growth and reproduction. Sibley notes that ROP18's primary role in T. gondii virulence suggests that similar genes in malaria parasites may be worthy of further study.

Sibley and his colleagues are currently working to identify ROP18's targets in the host cell. They are also looking for other genes that act together with ROP18 to contribute to T. gondii virulence.

“In addition, we plan to use the same genomic approaches that identified ROP18 to seek genes in T. gondii that affect other important characteristics, such as latency and transmissibility,” he says.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.wustl.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

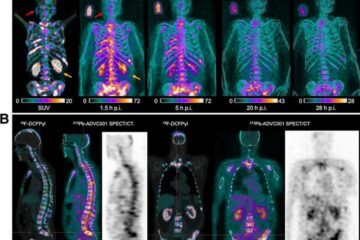

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…