MRSA use amoeba to spread, sidestepping hospital protection measures, new research shows

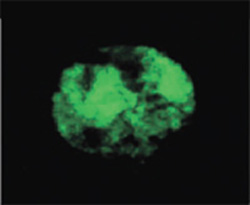

Microscope image of an amoeba with epidemic MRSA stained green

The MRSA ‘superbug’ evades many of the measures introduced to combat its spread by infecting a common single-celled organism found almost everywhere in hospital wards, according to new research published in the journal Environmental Microbiology.

Scientists from the University of Bath have shown that MRSA infects and replicates in a species of amoeba, called Acanthamoeba polyphaga, which is ubiquitous in the environment and can be found on inanimate objects such as vases, sinks and walls.

As amoeba produce cysts to help them spread, this could mean that MRSA maybe able to be ‘blown in the wind’ between different locations.

Further evidence from research on other pathogens suggests that by infecting amoeba first, MRSA may emerge more virulent and more resistant to antibiotics when it infects humans.

“Infection control policies for hospitals should recognise the role played by amoeba in the survival of MRSA, and evaluate control procedures accordingly,” said Professor Mike Brown from the Department of Pharmacy and Pharmacology at the University of Bath.

“Until now this source of MRSA has been totally unrecognised. This is a non-patient source of replication and given that amoeba and other protozoa are ubiquitous, including in hospitals, they are likely to contribute to the persistence of MRSA in the hospital environment”.

“Adding to the concern is that amoebal cysts have been shown to trap pathogens and could potentially be dispersed widely by air currents, especially when they are dry.

“Replication of MRSA in amoeba and other protozoa raises several important concerns for hospital hygiene.”

In laboratory tests, the researchers found that within 24 hours of its introduction, MRSA had infected around 50 per cent of the amoeba in the sample, with 2 per cent heavily infected throughout their cellular content.

Evidence with other pathogens suggests that pathogens that emerge from amoeba are more resistant to antibiotics and more virulent.

“This makes matters even more worrying,” said Professor Brown.

“It is almost as though the amoeba act like a gymnasium; helping MRSA get fitter and become more pathogenic.

“In many ways this may reflect how this kind of pathogenic behaviour first evolved. A good example is the bacterium that causes legionnaires disease. Probably it was pathogenic long before humans and other animals arrived on the evolutionary scene. Even today, it has no known animal host.

“The most likely reason is that Legionella and many pathogens learned their pathogenicity after sparring with single-celled organisms like amoeba for millions of years. Because our human cells are very similar to these primitive, single-celled organisms, they have acquired the skills to attack us”.

For these reasons, such primitive cells are being used to replace animals for many kinds of biological tests.

“Effective control of MRSA within healthcare environments requires better understanding of their ecology,” said Professor Brown.

“We now need to focus on improving our understanding of exactly how MRSA is transmitted, both in hospitals and in the wider environment, to develop control procedures that are effective in all scenarios.”

Recently released figures show that infections caused by MRSA rose 5 per cent between 2003 and 2004, and mortality rates increased 15-fold between 1993 and 2002.

The research paper is published online at:

http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.00991.x

It will appear in the June or July print issue of Environmental Microbiology which will be published mid-May or mid-June respectively.

The work was funded by The Lord Dowding Fund for Humane Research and also the UK Department of Health.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.bath.ac.uk/news/articles/releases/mrsaamoeba280206.htmlAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Security vulnerability in browser interface

… allows computer access via graphics card. Researchers at Graz University of Technology were successful with three different side-channel attacks on graphics cards via the WebGPU browser interface. The attacks…

A closer look at mechanochemistry

Ferdi Schüth and his team at the Max Planck Institut für Kohlenforschung in Mülheim/Germany have been studying the phenomena of mechanochemistry for several years. But what actually happens at the…

Severe Vulnerabilities Discovered in Software to Protect Internet Routing

A research team from the National Research Center for Applied Cybersecurity ATHENE led by Prof. Dr. Haya Schulmann has uncovered 18 vulnerabilities in crucial software components of Resource Public Key…