Core code cracked

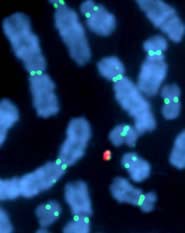

Stuck in the middle: centromeres’ repeats had the sequencers foxed. <br>H. Willard et al.

Sequencers expose secret chromosome centre.

February’s celebrations hid a dark secret: the human genome sequencers hadn’t touched the hearts of our chromosomes. Now, at last, one chromosome’s inscrutable midpoint, its centromere, has given up its genetic secrets.

Centromeres look like the ’waist’ in an X. They share out chromosomes fairly when a cell divides. Defective centromeres may underlie many cancers, in which problems with chromosome movement at cell division are common.

Unfortunately, repetitive sections in these regions confuse genome supercomputers – it’s like struggling with an expanse of blue sky in a jumbo jigsaw puzzle.

“It’s taken 15-20 years in different organisms to chase down,” says Huntington Willard of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. He and his team have painstakingly mapped the centromere of the human X chromosome1.

The centromere consists of a recurring 171-letter sequence, called alpha satellite DNA. The team used the rare differences between one repeat and the next to fit them together. “It’s like leading yourself hand over hand by a rope,” says Willard. Three million letters of these repeats is enough to make a working centromere, they show, proving that they’ve identified the real thing.

The group also compared sequences that bookend the alpha repeats with equivalent sections in primates. One part of an ancestral primate centromere is amplified in humans, they found.

The work “gives a clear picture of how [the centromere] might have evolved”, says chromosome researcher William Brown of the University of Nottingham, UK. “It grew relatively recently in human evolution.”

Even with the sequence in hand, no one knows how centromeres work. Unlike genes, which tend to be similar between organisms, centromeres are totally different in yeast, plants and flies. This suggests that the sequence itself is not very important.

How the DNA is packaged with proteins into a three-dimensional structure may make the centromere what it is, explains centromere expert Gary Karpen of the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California. Researchers are now trying to tease apart the proteins involved.

Other repetitive regions with few genes remain as unexplored ’black holes’ in the genome, says Karpen. “It’s tough going,” he says, nevertheless adding: “This demonstrates that they can be studied.”

References

- Schueler, M.G., Higgins, A.W., Rudd, M.K., Gustashaw, K. & Willard, H.F. Genomic and genetic definition of a functional human centromere. Science, 294, 109 – 115, (2001).

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nature.com/nsu/011011/011011-1.htmlAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…