Penn study finds a new role for RNA in human immune response

Findings could lead to new types of therapeutic RNAs for cancer, genetic diseases

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine have published the first study to test the role of RNA chemical modifications on immunity. They have demonstrated that RNA from bacteria stimulates immune cells to orchestrate destruction of invading pathogens. Most RNA from human cells is recognized as being self and does not stimulate an immune response to the same extent as invading bacteria or viruses. The researchers hypothesize that if this self-recognition fails, then autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus could result.

The research was a collaborative work led by Drew Weissman, MD, PhD, of the Division of Infectious Diseases and Katalin Karikó, PhD, of the Department of Neurosurgery. The investigators published their findings in the August issue of Immunity. “We think this study will open a new area of research in understanding how our immune systems protect us,” says Weissman.

“One application of our findings is that scientists will be able to design better therapeutic RNAs, including anti-sense or small-interfering RNAs, for treating diseases such as cancer and single-gene genetic diseases,” says Karikó.

RNA is the genetic material that programs cells to make proteins from DNA’s blueprint and specifies which proteins should be made. There are many types of RNA in the cells of mammals, such as transfer RNA, ribosomal RNA, messenger RNA, and all of them have specific types of chemical tags, or modifications. In contrast, RNAs from bacteria have fewer or no modifications.

Another type of RNA in mammalian cells is found in mitochondria, the powerhouses of cells. Mitochondrial RNA is thought to have originated from bacteria millions of years ago. Similar to RNA from bacteria, mitochondrial RNA has fewer chemical tags. It is the absence of modifications that causes RNA from bacteria and mitochondria to activate the immune response. The researchers suggest that these modifications have evolved in animals as one of the ways for the innate immune system to discriminate self from non-self.

When a tissue is damaged by injury, infection, or inflammation, cells release their mitochondrial RNA. This RNA acts as a signal to the immune system to recognize the damage and help defend and repair the tissue.

Conversely, the presence of the modifications on the other types of RNA does not activate an immune response and thus allows the innate immune system to discriminate self from non-self. “We showed that special proteins on the surface of immune cells, called Toll-like receptors, are instrumental in recognizing bacterial and mitochondrial RNA,” explains Weissman. The amount of modification on the RNA is important because as little as one or two tags per RNA molecule could prevent or suppress the immune reaction.

The authors concluded that the potential of RNA to activate immunity seems to be inversely correlated with the extent of its chemical modification and may explain why some viral RNA that is overly modified evades immune surveillance. The authors plan to investigate whether longer RNAs with specific tags will be useful for delivering therapeutic molecules to diseased cells.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uphs.upenn.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Eruption of mega-magnetic star lights up nearby galaxy

Thanks to ESA satellites, an international team including UNIGE researchers has detected a giant eruption coming from a magnetar, an extremely magnetic neutron star. While ESA’s satellite INTEGRAL was observing…

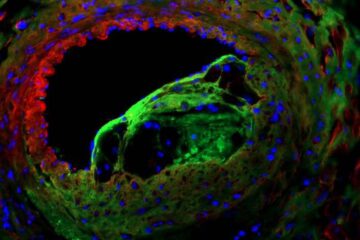

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…