Keeping cancer in check

Penn researchers demonstrate that a metabolic enzyme works through the tumor-suppressor protein p53 to control cellular replication

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine have identified in normal cells that a common metabolic enzyme, which acts as a rheostat of cellular conditions, also controls cell replication. This control is managed through p53, the much-studied protein implicated in many types of cancer. The discovery of the interaction between these two molecules may lead to new ways to fight cancer. First author Russell G. Jones, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of senior author Craig Thompson, MD, at the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute at Penn, and colleagues describe their findings in the most recent issue of Molecular Cell.

This work tests the novel notion that cancer cells co-opt cellular pathways that govern metabolism in order to proliferate beyond a cell’s normal means. Cancer cells have, by definition, a high metabolic rate and consume glucose at a high rate. One of the fundamental questions being tested in the Thompson lab is the importance of metabolism in cancer and investigating how cancer cells differ from normal cells, allowing them to survive and replicate. (Thompson is the Chair of Penn’s Department of Cancer Biology and Scientific Director of the Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute.) “We think that the enzyme interprets the energetic environment of the cell,” explains Jones. “It senses the stress a cell sees – such as low oxygen, low glucose, or the presence of free radicals – and, from this, can induce a check on replication through p53, acting in effect as a tumor-suppressor.”

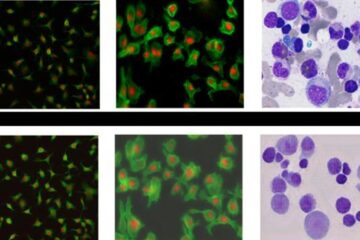

For this study, the investigators looked at noncancerous mouse cells called fibroblasts to see how normal cells work and what they do physiologically when faced with an environmental challenge: in this case, low glucose levels, explains Jones. When the enzyme – called AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) – is turned on, it prevents cells from replicating. It acts as a sensor to detect energy levels in a cell. When the cell experiences energy-limiting conditions, which is typified by low glucose, it uses more energy than it produces and enters into an energy-deficit state. In essence, AMPK acts as a “fuel gauge,” letting a cell know when glucose levels are dangerously low. When AMPK is activated by low glucose levels, it stops cells from replicating.

But how is p53 implicated? Normally p53 is activated in response to stress, and it stops a cell from replicating through a complicated set of biochemical steps. For example, if a cell is hit by radiation, enzymes called kinases activate p53, leading to inhibition of cell replication. “We found that cells without p53 due to a mutation would continue to proliferate under low glucose conditions, bypassing the AMPK checkpoint,” says Jones. The lab is now doing follow-up studies and is finding that when AMPK is activated in a tumor cell that has no active p53, it still proliferates, escaping the AMPK checkpoint. This avenue of study may one day provide another approach to treating cancer, the researchers surmise.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uphs.upenn.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…