DNA-repair protein functions differently in different organisms

Researchers hope to someday develop an enzyme to repair UV-damaged DNA in humans

Plants, pond scum, and even organisms that live where the sun doesn’t shine have something that humans do not — an enzyme that repairs DNA damaged by ultraviolet (UV) light.

Cabell Jonas of Richmond, Va., an undergraduate honors student in biology at Virginia Tech, will report on the molecular details of the DNA-repair enzyme at the 225th national meeting of the American Chemical Society March 23-27 in New Orleans. Her poster includes the novel discovery that the enzyme does not operate the same way in different organisms.

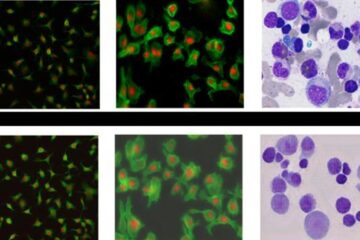

UV light is one of the most prevalent causes of DNA damage. In humans, incidents of resulting disease — in particular, skin cancer, are increasing as exposure to UV increases, says Sunyoung Kim, assistant professor of biochemistry at Virginia Tech. Since the human body does not have DNA photolyase, Kim and her students are studying the DNA-repair enzyme in other systems. “Our aim is to map the molecular interactions and understand the structural changes, with the eventual goal of being able to create or adapt this flavoenzyme from another organism for treatment of skin cancer in humans,” says Kim.

She explains that there are two different kinds of DNA repair. One is base incision repair — the cell machinery gears up, cuts out the damaged section of DNA, and rebuilds it. The second uses DNA photolyase. “A Lone Ranger enzyme repairs the damage without all the machinery or a lot of team players.”

In two steps — photoactivation and photo repair — the flavoenzyme actually uses light to repair UV damage — but from a different, visible part of the spectrum. During activation, a flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) molecule triggers a transfer of electrons from the flavin portion of the enzyme to the damaged DNA to carry out repair.

“We’ve discovered that, depending on which organism the enzyme comes from, the transfer of electrons through the protein is a little different,” says Kim. “That is novel because it is generally assumed — and is a basis for bioinformatics, for instance — that the same protein doing the same job, even in different organisms, performs in the same way. But we are finding that this job of DNA repair is done by slightly different proteins in our two model organisms — e. coli and cyanobacterium (once known as blue-green algae) — and that the electrons take different paths to perform the repair.”

The poster, “Examination of photoactivation in DNA photolyase using difference infrared spectroscopy (CHED 893),” by Jonas, graduate student Lori A. McKee of Butte, Montana, and Kim, will be presented on Monday, March 24, from 2 to 4 p.m. in Convention Center Hall J. Now a senior, Jonas has carried out research in Dr. Kim’s lab since Jonas was a sophomore. McKee received her undergraduate chemistry degree at Montana Tech.

Contact Dr. Kim at sukim1@vt.edu or (540)231-8636 or Cabell Jonas at mjonas@vt.edu(540)231-7091.

PR Contact: Susan Trulove, 540-231-5646, strulove@vt.edu

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.technews.vt.edu/All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…