Models Begin to Unravel How Single DNA Strands Combine

Present in the cells of all living organisms, DNA is composed of two intertwined strands and contains the genetic “blueprint” through which all living organisms develop and function. Individual strands consist of nucleotides, which include a base, a sugar and a phosphate moiety.

Understanding hybridization, the process through which single DNA strands combine to form a double helix is fundamental to biology and central to technologies such as DNA microchips or DNA-based nanoscale assembly. The research by the Wisconsin group begins to unravel how DNA strands come together and bind to each other, says Juan J. de Pablo, UW-Madison Howard Curler Distinguished Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering.

The team published its findings today (Oct. 5), in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In addition to senior author de Pablo, the group included David C. Schwartz, a UW-Madison professor of chemistry and genetics, and former postdoctoral research fellow Edward J. Sambriski, now an assistant professor of chemistry at Delaware Valley College in Pennsylvania.

The three drew on detailed molecular DNA models developed by de Pablo’s research group to study the reaction pathways through which double-stranded DNA undergo denaturation, where the molecule uncoils and separates into single strands, and hybridization, through which complementary DNA strands bind, or “hybridize.” In Watson-Crick base pairing, A (adenine) pairs with T (thymine), while G (guanine) pairs with C (cytosine). Reaction pathways are the trajectories single DNA strands follow to find each other and connect via such complementary pairs.

The researchers studied both random and repetitive base sequences. Random sequences of the four bases — A, T, G and C — contained little or no regular repetition. To the researchers’ surprise, a couple of bases located toward the center of the strand associate early in the hybridization process. The moment they find each other, they bind and the entire molecule hybridizes rapidly and in a highly organized manner.

Conversely, in repetitive sequences, the bases alternated regularly, and the group found that these sequences bind through a so-called diffusive process. “The two strands of DNA somehow find each other, they connect to each other in no particular order, and then they slide past each other for a long time until the exact complements find one another in the right order, and then they hybridize,” says de Pablo.

Results of the team’s study show that DNA hybridization is very sensitive to DNA composition, or sequence. “Contrary to what was thought previously, we found that the actual process by which complementary DNA strands hybridize is very sensitive to the sequence of the molecules,” he says.

Knowledge of how the process occurs could enable researchers to more strategically design technologies such as gene chips. For example, says de Pablo, if a researcher wanted to design sequences that bind very rapidly or with high efficiency, he or she could place certain bases in specific locations, so that the hybridization reaction could occur faster or more reliably.

Ultimately, the research could help biologists understand why some hybridization reactions are faster or more robust than others. “One of the really exciting things about this work is that the hybridization reaction between two strands of DNA is really fundamental to life itself,” says de Pablo. “It is the basis for much of biology. And it is amazing to me that, until now, we knew little of how this reaction actually proceeds.”

The National Science Foundation-funded Nanoscale Science and Engineering Center on Templated Synthesis and Assembly at the Nanoscale at UW-Madison sponsored the research.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.wisc.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

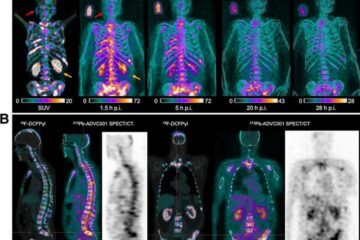

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…