In the Jaws of Venus Flytrap

The carnivorous Venus flytrap snaps shut with its plate-shaped trapping leaves. The mouth first becomes a "green stomach" and then an intestine.<br>Picture: Christian Wiese<br><br>

In order to obtain vital nitrogen from its prey, the plant uses a previously unknown mechanism, discovered by researchers from Würzburg, Freiburg and Göttingen.

Nitrogen is a key nutrient for plants. They usually extract it from the soil in the form of nitrate or ammonium, which is transported to the roots and leaves to be used for the formation of proteins.

But what are plants to do if the soil provides little or no nitrogen? The carnivorous Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipula), which is native to some swamplands of North America, has adapted to such nutrient-poor environments. It is able to survive there only because it has specialized in getting additional nutrients from animals.

How Dionaea catches its prey

Dionaea catches its prey with leaves that have evolved into snap-traps: If the insects touch special sensitive hairs on the surface of the trap, electrical impulses are triggered, causing the trap to snap shut in a flash.

Obviously, the trapped animals will try to escape. However, the more ferociously they fight, the more frequently they will touch the sensitive hairs. This in turn triggers a barrage of electrical impulses and initiates the production of the lipid hormone. The hormone activates numerous glands, which are densely packed on the inside of the trap: They flood the “green stomach” with an acidic fluid, containing more than 50 different digestive enzymes.

The digestive process is described in detail by the biophysicist Rainer Hedrich and his team in the journal “Current Biology”. As described there, the trap of the plant integrates the functions of mouth, stomach and intestine into one single unit: “The glands that first secrete the enzyme-rich acidic digestive fluid take in the nutritious animal components later,” Hedrich explains. “When the stomach is empty, the mouth opens in order to strike again at the next possible opportunity.”

How the nitrogen is made available

The researchers analyzed the stomach contents of the Venus flytrap and found out that the body of the prey is broken down into its protein components, the amino acids. They noticed that the amino acid glutamine was missing and that the nitrogenous mineral nutrient ammonium was present instead. The reason: “The digestive fluid of the plant contains an enzyme, which breaks down the glutamine into glutamate and ammonium. The latter is then absorbed by the glands that have previously released the digestive fluid,” says Hedrich.

The fact that plants are able to extract ammonium from animal proteins in this way was previously unknown. Apart from Hedrich's team, the research leading to this discovery involved Heinz Rennenberg of the University of Freiburg – an expert on nitrogen uptake and metabolism – and Erwin Neher. The Nobel laureate at the University of Göttingen is an expert on secretion processes.

What the lipid hormone brings about

In their experiments, the researchers discovered some additional facts: If a trap of the carnivorous plant has not caught and dissolved any insect prey, its “intestine” does not work: In this case, it cannot take in ammonium efficiently.

But this changes if the lipid hormone is previously applied to the trap. “The hormone has the effect that the gland cells are equipped with an ammonium transporter, which conveys the desired nitrogenous molecule into the plant,” says Hedrich. The scientists also identified and named the gene responsible: DmAMT1 (Dionaea-muscipula-Ammonium-Transporter1).

What the researchers are going to do next

Besides nitrogen, all organisms need many more key nutrients and trace elements. How does the Venus flytrap extract sulfur and phosphorus from its prey? And in which form does it absorb these nutrient elements? How does the plant determine the current filling level of its stomach? Does it use the nourishment from the prey for the development of new trapping organs or for the production of new roots as well? And what happens when the root gets in contact with nutrients? These are the questions that the scientists are going to answer next.

In 2010, Rainer Hedrich was awarded a European research grant for this project, namely the ERC Advanced Grant, which is worth 2.5 million euro. The research topic is sensation, predatory behavior and prey digestion of Venus flytrap. Its genome is also to be decoded in order to determine the molecular principles of the carnivorous processes in plants.

Scherzer et al., The Dionaea muscipula Ammonium Channel DmAMT1 Provides NH4+ Uptake Associated with Venus Flytrap’s Prey Digestion, Current Biology (2013), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.07.028

Contact person

Prof. Dr. Rainer Hedrich, Julius-von-Sachs-Institute for Biosciences at the University of Würzburg, T +49 (0)931 31-86100, hedrich@botanik.uni-wuerzburg.de

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.uni-wuerzburg.deAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

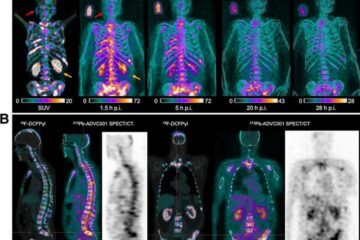

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…