Insight into the evolution of parasitism

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology, together with American colleagues, have decoded the genome of the Pristionchus pacificus nematode, thereby gaining insight into the evolution of parasitism.

In their work, which has been published in the latest issue of Nature Genetics, the scientists from Professor Ralf J. Sommer's department in Tübingen, Germany, have shown that the genome of the nematode consists of a surprisingly large number of genes, some of which have unexpected functions.

These include a number of genes that are helpful in breaking down harmful substances and for survival in a strange habitat: the Pristionchus uses beetles as a hideout and as means of transport, and feeds on the fungi and bacteria that spread out on their carcasses once they have died. It thus provides the clue to understanding the complex interactions between host and parasite. (Nature Genetics, Advance online publication, 21.09.2008, doi: 10.1038/ng.227)

With well over a million different species, nematodes are the largest group in the animal kingdom. The worms, usually only just one millimetre in length, are found on all continents and in all ecosystems on Earth. Some, as parasites, are major pathogens to humans, animals and plants. Within the group of nematodes, at least seven forms of parasitism have developed independently from one another. One member of the nematode group has acquired a certain degree of fame: due to its humble lifestyle, small size and quick breeding pattern, Caenorhabditis elegans is one of the most popular animals being used as models in biologists' laboratories. It was the first multicellular animal whose genome was completely decoded in 1998.

Ten years later, a group of scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology in Tübingen (Germany), together with researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute in St. Louis (USA), have now presented the genome of another species of nematode, the model organism Pristionchus pacificus. Pristionchus species have carved out a very particular habitat for themselves: they live together with May beetles, dung beetles and potato beetles in order to feast on the bacteria and fungi that develop on the carcasses of these beetles after they have died. The nematodes therefore use the beetles as a mobile habitat that offers them shelter and food.

When they move from the land to the beetle, the nematodes' habitat changes dramatically. The nematodes have to protect themselves against toxic substances in their host, for example. The methods they employ to cope with the conditions in the beetle are worthy of closer attention, as this life form can possibly be regarded as the precursor to real parasites. At least, this is what researchers have suspected for a long time.

The sequencing of the genome of Pristionchus pacificus has now confirmed this suspicion: the genome, consisting of around 170 megabases, contains more than 23,500 protein-coding genes. By comparison, the model organism of Caenorhabditis elegans and the human parasite Brugia malayi (whose genome was sequenced in 2007) only have about 20,000 or 12,000 protein-coding genes, respectively. “The increase in Pristionchus is partly attributable to gene duplications,” explained Ralf Sommer. “These include a number of genes that could be helpful for breaking down harmful substances and for survival in the complex beetle ecosystem.”

Surprisingly, the Pristionchus genome also has a number of genes that are not known in Caenorhabditis elegans, although they have been found in plant parasites. Genes for cellulases – enzymes that are required to break down the cell walls of plants and microorganisms – have aroused particular interest among scientists. “The really exciting questions are still to come”, said Sommer. “Using the sequence data, we can test how Pristionchus has adapted to its specific habitat. And this will undoubtedly give us new insight into the evolution of parasitism.”

Original publication

Dieterich, C., Clifton, S. W., Schuster, L., Chinwalla, A., Delehaunty, K., Dinkelacker, I., Fulton, L., Fulton, R., Godfrey, J., Minx, P., Mitreva, M., Roeseler, W., Tian, H., Witte, H., Yang, S.-P., Wilson, R. K. & Sommer R. J. (2008): The Pristionchus pacificus genome provides a unique perspective on nematode lifestile and parasitism. Nature Genetics, Advance Online Publication, September 21, 2008, doi:10.1038/ng.227.

Contact

Prof. Dr. Ralf J. Sommer

Phone: +49 (0)7071-601-371

e-mail: Ralf.Sommer@tuebingen.mpg.de

Dr. Susanne Diederich (Press and Public Relations Department)

Phone: +49 (0)7071-601-333

e-mail: presse@tuebingen.mpg.de

The Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology conducts basic research in the fields of biochemistry, genetics and evolutionary biology. It employs about 325 people and is located at the Max Planck Campus in Tuebingen, Germany. The Max Planck Institute for Developmental Biology is one of 82 research and associated institutes of the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

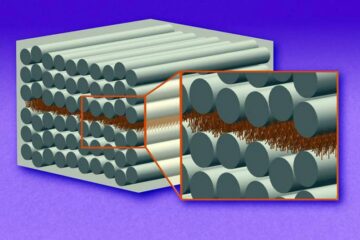

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…

Trash to treasure

Researchers turn metal waste into catalyst for hydrogen. Scientists have found a way to transform metal waste into a highly efficient catalyst to make hydrogen from water, a discovery that…

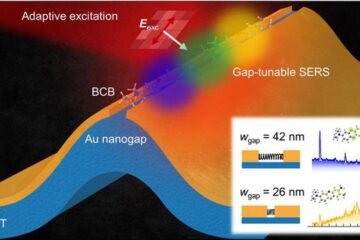

Real-time detection of infectious disease viruses

… by searching for molecular fingerprinting. A research team consisting of Professor Kyoung-Duck Park and Taeyoung Moon and Huitae Joo, PhD candidates, from the Department of Physics at Pohang University…