New ground broken on aggression research

“I looked at the gene that makes the body's testosterone detector to determine if variations in this detector's sensitivity to the chemical causes people to be more or less aggressive,” said Hurd.

Hurd came across a previously published study in India that found violent criminals had genes that made receptors that were very sensitive to the presence of testosterone, so he decided to conduct a similar experiment with volunteers at the U of A.

“Using survey questions and DNA analysis, we came up with exactly the opposite finding from the study done in India,” explained Hurd. “In our samples, less sensitive genes indicated more aggressive behaviour, perhaps because the bodies of those people wound up producing more testosterone to compensate.”

Hurd said it can be likened to smoke detectors; a less sensitive device requires more smoke in a room than a very sensitive one. Hurd believes that testosterone levels and sensitivity are particularly important during fetal development, particularly since testosterone acts to influence fetal brain development indirectly, through a different receptor after it has been converted to a slightly different chemical. “More or less prenatal testosterone seems to have consequences throughout a person's entire lifetime.”

Hurd says there seems to be a link between fetal testosterone and social behaviour, like aggression, in adults, and that the effects of the variation in sensitivity on the levels of fetal testosterone may explain the effect seen.

Hurd says the varying levels of testosterone sensitivity or exposure seen in the U of A volunteers is not related to extremely aggressive or criminal behaviour. “It's not as though these people were unable to physically control their emotions, it's much more subtle than that.”

In fact, Hurd says the elevated aggression within this sample of students includes displays of aggression by one person against individuals through use of subtle, “gossip girl” styles of indirect aggression. “That kind of subtle aggression could involve getting back at a perceived enemy by talking to others about them behind their back.”

The work of Hurd, Kathryn Vaillancourt and Natalie Dinsdale was published in the journal Behavior Genetics.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ualberta.caAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Bringing bio-inspired robots to life

Nebraska researcher Eric Markvicka gets NSF CAREER Award to pursue manufacture of novel materials for soft robotics and stretchable electronics. Engineers are increasingly eager to develop robots that mimic the…

Bella moths use poison to attract mates

Scientists are closer to finding out how. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are as bitter and toxic as they are hard to pronounce. They’re produced by several different types of plants and are…

AI tool creates ‘synthetic’ images of cells

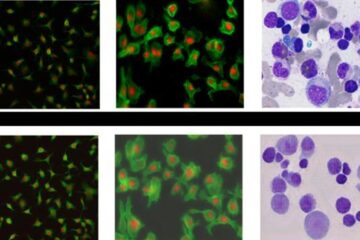

…for enhanced microscopy analysis. Observing individual cells through microscopes can reveal a range of important cell biological phenomena that frequently play a role in human diseases, but the process of…