From worm muscle to spinal discs – An evolutionary surprise

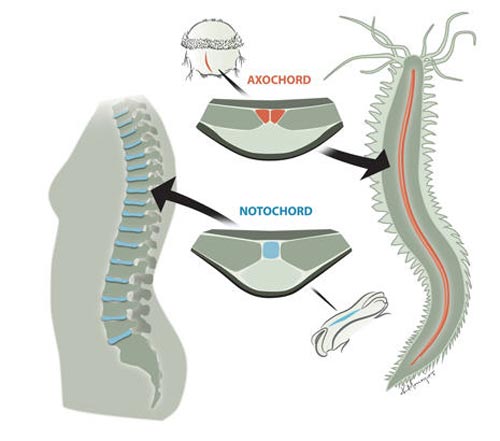

The marine worm Platynereis has a muscle (red) which develops in the same place and has the same genetic signature as the notochord (blue) that develops into our spinal discs. Credit: Kalliopi Monoyios

Scientists at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, have found that, unexpectedly, this skeleton most likely evolved from a muscle. The study, carried out in collaboration with researchers at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Janelia Farm, USA, is published today in Science.

Humans are part of a group of animals called chordates, whose defining feature is a rod of cartilage that runs lengthwise along the middle of their body, under their spinal chord. This structure, called the notochord, was the first vertebrate skeleton.

It is present in human embryos, and is replaced with the backbone as we develop, with the cartilage reduced to those tell-tale discs. Since starfish, sea urchins and related animals have no such structure, scientists assumed the notochord had emerged in a relatively recent ancestor, after our branch of the evolutionary tree split away from the ‘starfish branch’.

“People simply haven’t been looking beyond our direct relatives, but that means you could be fooled, if the structure appeared earlier and that single group lost it,” says Detlev Arendt from EMBL, who led the study. “And in fact, when we looked at a broader range of animals, this is what we found.”

Antonella Lauri and Thibaut Brunet, both in Arendt’s lab, identified the genetic signature of the notochord – the combination of genes that have to be turned on for a healthy notochord to form. When they found that the larva of the marine worm Platynereis dumerilii has a group of cells with that same genetic signature, the scientists teamed up with Philipp Keller’s group at Janelia Farm to use state-of-the-art microscopy to follow those cells as the larva developed.

They found that the cells form a muscle that runs along the animal’s midline, precisely where the notochord would be if the worm were a chordate. The researchers named this muscle the axochord, as it runs along the animal’s axis. A combination of experimental work and combing through the scientific literature revealed that most of the animal groups that sit between Platynereis and chordates on the evolutionary tree also have a similar, muscle-based structure in the same position.

The scientists reason that such a structure probably first emerged in an ancient ancestor, before all these different animal groups branched out on their separate evolutionary paths. Such a scenario would also explain why the lancelet amphioxus, a ‘primitive’ chordate, has a notochord with both cartilage and muscle. Rather than having acquired the muscle independently, amphioxus could be a living record of the transition from muscle-based midline to cartilaginous notochord.

The shift from muscle to cartilage could have come about because a stiffened central rod would make swimming more efficient, the scientists postulate.

Published online in Science on 12 September 2014. DOI: 10.1126/science.1253396.

For images, video and more information please visit: www.embl.org/press/2014/140911_Heidelberg

Policy regarding use

EMBL press and picture releases including photographs, graphics and videos are copyrighted by EMBL. They may be freely reprinted and distributed for non-commercial use via print, broadcast and electronic media, provided that proper attribution to authors, photographers and designers is made.

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…