CSHL team solves structure of NMDA receptor unit that could be drug target for neurological diseases

A team of scientists at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) reports on Thursday their success in solving the molecular structure of a key portion of a cellular receptor implicated in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and other serious illnesses.

Assistant Professor Hiro Furukawa, Ph.D., and colleagues at CSHL, in cooperation with the National Synchrotron Light Source at Brookhaven National Laboratory, obtained crystal structures for one of several “subunits” of the NMDA receptor. This receptor, formally called the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, belongs to a family of cellular receptors that mediate excitatory nerve transmission in the brain.

Excitatory signals represent the majority of nerve signals in most regions of the human brain. One theory of causation in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and multiple sclerosis posits that excessive amounts of the excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, can cause an overstimulation of glutamate receptors, including the NMDA receptor. Such excitotoxicity, the theory holds, can cause nerve-cell death and subsequent neurological dysfunction.

A class of inhibitors of the NMDA receptor under the generic name Memantine has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for use in moderate and severe cases of Alzheimer's. Memantine is a non-specific inhibitor of the NMDA receptor and is neither a cure nor an agent that can halt progression of the disease. The search is well under way for molecules that can shut down the NMDA receptor with much greater specificity. The CSHL team's work pertains directly to that effort.

The NMDA receptor is modular, composed of multiple domains with distinct functional roles. Part of the receptor is lodged in the membrane of nerve cells and part juts out from the membrane. Furukawa's CSHL team focused on a portion of the so-called extracellular domain of the receptor, a subunit called NR2B, which includes a domain of particular interest called the ATD (the amino terminal domain).

“This part is of great interest to us because it has very little in common with ATDs in other kinds of glutamate receptors involved in nerve transmission,” says Furukawa. Its uniqueness makes it a potentially interesting target for future drugs. “Our interest is even keener because we already know there are a rich spectrum of small molecules that can bind the ATD of NMDA receptors.”

Without a highly detailed molecular picture of the ATD, however, efforts to rationally design inhibitors cannot proceed. Hence the importance of Furukawa's achievement: a crystal structure revealed by the powerful light source at Brookhaven National Laboratory, that shows the ATD to have a “clamshell”-like appearance that is important for its function. The results are published in a paper appearing online Thursday ahead of print in The EMBO Journal, the publication of the European Molecular Biology Organization.

The team obtained structures of the ATD domain with and without zinc binding to it. Zinc is a natural ligand that docks at a spot within the “clamshell” in routine functioning of the NMDA receptor. Of much greater interest is the location and nature of a suspected binding site of a small molecule type that is known to bind the ATD and inhibit the action of the NMDA receptor.

These inhibitor molecules are members of a class of compounds called phenylethanolamines which “have high efficacy and specificity and show some promise as neuroprotective agents without side effects seen in compounds that bind at the extracellular domain of other receptors,” Furukawa explains. Now that his team has solved the structure of the ATD domain of the NR2B subunit, it becomes possible to proceed with rational design of a phenylethanolamine-like compound that can precisely bind the ATD within what Furukawa and colleagues call its “clamshell cleft,” based on the crystal structure they have obtained.

“Structure of the Zinc-bound Amino-terminal Domain of the NMDA receptor NR2B subunit” will be published online ahead of print November 12 in The EMBO Journal. The authors are: Erkan Karakas, Noriko Simorowski, and Hiro Furukawa. The paper will be available online Nov. 12 at: http://www.nature.com/emboj/journal/vaop/ncurrent/index.html

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) is a private, not-for-profit research and education institution at the forefront of efforts in molecular biology and genetics to generate knowledge that will yield better diagnostics and treatments for cancer, neurological diseases and other major causes of human suffering.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.cshl.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

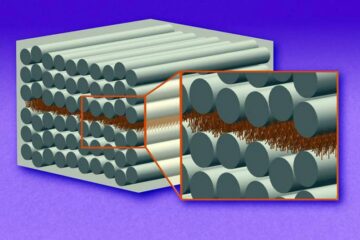

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…

Trash to treasure

Researchers turn metal waste into catalyst for hydrogen. Scientists have found a way to transform metal waste into a highly efficient catalyst to make hydrogen from water, a discovery that…

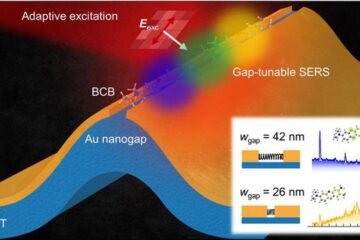

Real-time detection of infectious disease viruses

… by searching for molecular fingerprinting. A research team consisting of Professor Kyoung-Duck Park and Taeyoung Moon and Huitae Joo, PhD candidates, from the Department of Physics at Pohang University…