Cell binding discovery brings hope to those with skin and heart problems

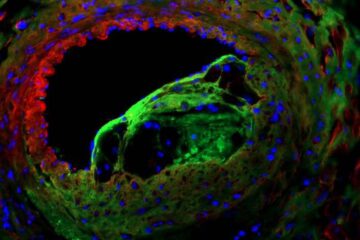

Professor David Garrod, in the Faculty of Life Sciences, has found that the glue molecules bind only to similar glue molecules on other cells, making a very tough, resilient structure. Further investigation on why the molecules bind so specifically could lead to the development of clinical applications.

Professor Garrod, whose Medical Research Council-funded work is paper of the week in the Journal of Biological Chemistry (JBC) tomorrow (Friday), said: “Our skin is made up of three different layers, the outermost of which is the epidermis. This layer is only about 1/10th of a millimetre thick yet it is tough enough to protect us from the outside environment and withstand the wear and tear of everyday life.

“One reason our epidermis can do this is because its cells are very strongly bound together by tiny structures called desmosomes, sometimes likened to rivets. We know that people who have defects in their desmosomes have problems with their epidermis and get extremely unpleasant skin diseases. Understanding how desmosomes function is essential for developing better treatments for these and other types of skin disease and for non-healing wounds.

“Desmosomes are also extremely important in locking together the muscle cells of the heart, and hearts where desmosomes are defective can fail catastrophically, causing sudden death in young people.

Hence our findings may also be relevant in the heart and in developing new treatments for heart disease.”

ProfessorGarrod and his team, Zhuxiang Nie, Anita Merritt, Mansour Rouhi and Lydia Tabernero, used chemical cross-linking to study cells of the epidermis and found what they believe to be the principal mechanism by which the glue molecules of desmosomes of skin cells bind to each other.

“For reasons that we do not fully understand there are several different but closely-related glue molecules within each desmosome,” he explained.

“Our results show that each glue molecule on one cell binds primarily to another of the same type on the neighbouring cell, meaning the binding is highly specific. This was very surprising because previous studies using different techniques had not been able to give such a clear answer on the specificity of binding.”

He added: “Our result suggests that this type of specific binding is of fundamental importance in locking together cells of the epidermis into a tough, resilient structure. It is an important step forward in our research, which aims to develop better treatments for non-healing wounds, other skin diseases and heart problems. We could do this if we understood how to make medicines that would lock or unlock the desmosomes as required.”

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.manchester.ac.ukAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Eruption of mega-magnetic star lights up nearby galaxy

Thanks to ESA satellites, an international team including UNIGE researchers has detected a giant eruption coming from a magnetar, an extremely magnetic neutron star. While ESA’s satellite INTEGRAL was observing…

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…