The Arctic: Interglacial period with a break

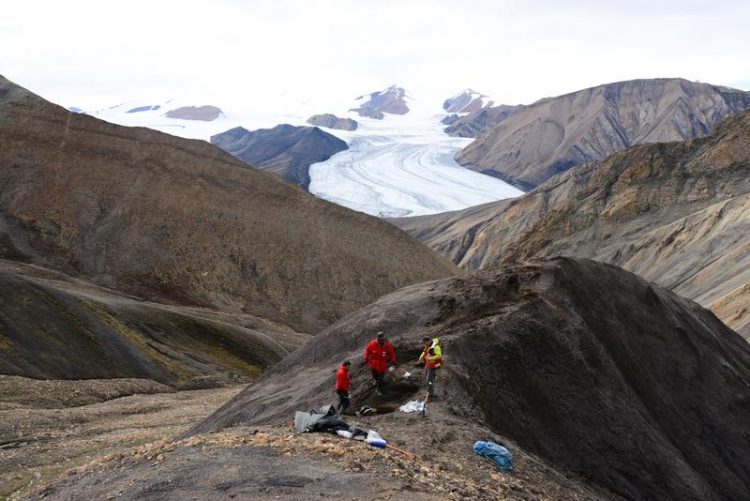

Beprobung kreidezeitlicher Sedimente am Lost Hammer Diapir auf Axel Heiberg Island. © Claudia Schröder-Adams

Scientists at the Goethe University Frankfurt and at the Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre working together with their Canadian counterparts, have reconstructed the climatic development of the Arctic Ocean during the Cretaceous period, 145 to 66 million years ago.

The research team comes to the conclusion that there was a severe cold snap during the geological age known for its extreme greenhouse climate. The study published in the professional journal Geology is also intended to help improve prognoses of future climate and environmental development and the assessment of human influence on climate change.

The Cretaceous, which occurred approximately 145 million to 66 million years ago, was one of the warmest periods in the history of the earth. The poles were devoid of ice and average temperatures of up to 35 degrees Celsius prevailed in the oceans.

“A typical greenhouse climate; some even refer to it as a 'super greenhouse' “, explains Professor Dr. Jens Herrle of the Goethe University and Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, and adds: “We have now found indications in the Arctic that this warm era 112 to 118 million years ago was interrupted for a period of about 6 million years.”

In cooperation with his Canadian colleague Professor Claudia Schröder-Adams of the Carleton University in Ottawa, the Frankfurt palaeontologist sampled the Arctic Fjord Glacier and the Lost Hammer diapir locality on Axel Heiberg Island in 5 to 10 metre intervals. “In so doing, we also found so-called glendonites”, Herrle recounts.

Glendonite refers to star-shaped calcite minerals, which have taken on the crystal shape of the mineral ikaite. “These so-called pseudomorphs from calcite to ikaite are formed because ikaite is stable only below 8 degrees Celsius and metamorphoses into calcite at warmer temperatures”, explains Herrle and adds:

“Thus, our sedimentological analyses and age dating provide a concrete indication for the environmental conditions in the cretaceous Arctic and substantiate the assumption that there was an extended interruption of the interglacial period in the Arctic Ocean at that time.”

In two research expeditions to the Arctic undertaken in 2011 and 2014, Herrle brought 1700 rock samples back to Frankfurt, where he and his working group analysed them using geochemical and paleontological methods. But can the Cretaceous rocks from the polar region also help to get a better understanding of the current climate change? “Yes”, Herrle thinks, elaborating: “The polar regions are particularly sensitive to global climatic fluctuations.

Looking into the geological past allows us to gain fundamental knowledge regarding the dynamics of climate change and oceanic circulation under extreme greenhouse conditions. To be capable of better assessing the current man-made climate change, we must, for example, understand what processes in an extreme greenhouse climate contribute significantly to climate change.”

In the case of the Cretaceous cold snap, Herrle assumes that due to the opening of the Atlantic in conjunction with changes in oceanic circulation and marine productivity, more carbon was incorporated into the sediments. This resulted in a decrease in the carbon dioxide content in the atmosphere, which in turn produced global cooling.

The Frankfurt scientist's newly acquired data from the Cretaceous period will now be correlated with results for this era derived from the Atlantic, “in order to achieve a more accurate stratigraphic classification of the Cretaceous period and to better understand the interrelationships between the polar regions and the subtropics”, is the outlook Herrle provides.

Publication

Jens O. Herrle, Claudia J., Schröder-Adams, William Davis, Adam T. Pugh, Jennifer M. Galloway, and Jared Fath: Mid-Cretaceous High Arctic stratigraphy, climate, and Oceanic Anoxic Events, in: Geology, 19 Mai 2015, 10.1130/G36439.1 Open Access

http://geology.gsapubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/G36439.1v1

Information: Prof. Dr. Jens O. Herrle, Senckenberg Biodiversity and Climate Research Centre, Faculty of Geoscience and Geography, Goethe University Frankfurt, Phone +49 (0)69 798 40180, jens.herrle@em.uni-frankfurt.de

Goethe University is a research-oriented university in the European financial centre Frankfurt founded in 1914 with purely private funds by liberally-oriented Frankfurt citizens. It is dedicated to research and education under the motto “Science for Society” and to this day continues to function as a “citizens’ university”. Many of the early benefactors were Jewish. Over the past 100 years, Goethe University has done pioneering work in the social and sociological sciences, chemistry, quantum physics, brain research and labour law. It gained a unique level of autonomy on 1 January 2008 by returning to its historic roots as a privately funded university. Today, it is among the top ten in external funding and among the top three largest universities in Germany, with three clusters of excellence in medicine, life sciences and the humanities.

Publisher: The President of Goethe University Frankfurt

Editor: Dr. Anke Sauter, Science Editor, International Communication, Phone +49(0)69 798-12498, Fax +49(0)69 798-761 12531, sauter@pvw.uni-frankfurt.de

Internet: www.uni-frankfurt.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Earth Sciences

Earth Sciences (also referred to as Geosciences), which deals with basic issues surrounding our planet, plays a vital role in the area of energy and raw materials supply.

Earth Sciences comprises subjects such as geology, geography, geological informatics, paleontology, mineralogy, petrography, crystallography, geophysics, geodesy, glaciology, cartography, photogrammetry, meteorology and seismology, early-warning systems, earthquake research and polar research.

Newest articles

Properties of new materials for microchips

… can now be measured well. Reseachers of Delft University of Technology demonstrated measuring performance properties of ultrathin silicon membranes. Making ever smaller and more powerful chips requires new ultrathin…

Floating solar’s potential

… to support sustainable development by addressing climate, water, and energy goals holistically. A new study published this week in Nature Energy raises the potential for floating solar photovoltaics (FPV)…

Skyrmions move at record speeds

… a step towards the computing of the future. An international research team led by scientists from the CNRS1 has discovered that the magnetic nanobubbles2 known as skyrmions can be…