Research Aims for Insecticide That Targets Malaria Mosquitoes

The insecticide would work by interfering with an enzyme found in the nervous systems of mosquitoes and many other organisms, called acetylcholinesterase.

Existing insecticides target the enzyme but affect a broad range of species, said entomologist Jeff Bloomquist, a professor in UF’s Emerging Pathogens Institute and its Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Acetylcholinesterase helps regulate nervous system activity by stopping electrical signaling in nerve cells. If the enzyme can’t do its job, the mosquito begins convulsing and dies. The research team’s goal is to develop compounds perfectly matched to the acetylcholinesterase molecules in malaria-transmitting mosquitoes, he said.

“A simple analogy would be that we’re trying to make a key that fits perfectly into a lock,” Bloomquist said. “We want to shut down the enzyme, but only in target species.”

Malaria is spread by mosquitoes in the Anopheles genus, notably Anopheles gambiae, native to Africa. The disease is common in poor communities where homes may not have adequate screens to keep flying insects out.

Malaria is caused by microscopic organisms called protists, which are present in the saliva of infected female mosquitoes and transmitted when the mosquitoes bite.

Initial symptoms of the disease can include fever, chills, convulsions, headaches and nausea. In severe cases, malaria can cause kidney failure, coma and death. Worldwide, malaria infected about 219 million people in 2010 and killed about 660,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. About 90 percent of those infected lived in Africa.

Bloomquist and colleagues at Virginia Tech, where the project is based, are trying to perfect mosquito-specific compounds that can be manufactured on a large scale and applied to mosquito netting and surfaces where the pests might land.

It will take at least four to five years before the team has developed and tested a compound enough that it’s ready to be submitted for federal approval, Bloomquist said.

The team recently published a study in the journal Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology comparing eight experimental compounds with commercially available insecticides that target the enzyme.

Though they were less toxic to mosquitoes than commercial products, the experimental compounds were far more selective, indicating researchers are on the right track, he said.

“The compounds we’re using are not very toxic to honeybees, fish and mammals, but we need to refine them further, make them more toxic to mosquitoes and safer for nontarget organisms,” he said.

Funding for the project came from a five-year, $3.6 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health.

In Florida, malaria was a significant problem in the early 20th century, transmitted by native Anopheles mosquitoes. The disease has been greatly curtailed via mosquito-control practices but even today, cases are occasionally reported in the Sunshine State.

Source: Jeff Bloomquist, jbquist@epi.ufl.edu, 352-273-9417

Writer: Tom Nordlie, tnordlie@ufl.edu, 352-273-3567

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ufl.eduAll latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

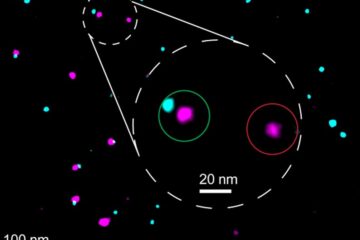

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…