’Live fast, die young’ true for forests too

Trees in the world¹s most productive forests — forests that add the most new growth each year — also tend to die young, according to a U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) study published in a recent issue of the journal Ecology Letters. This discovery could help scientists predict how forests will respond to ongoing and future environmental changes.

“One implication of this fast turnover rate is that the world¹s most productive forests may be those likely to respond most quickly to such things as climatic change,” said Nate Stephenson, a USGS research ecologist in Three Rivers, Calif., and lead author of the article.

“You can view a forest like a bank account,” said Stephenson. “As long as deposits and withdrawals are similar, your balance remains stable. But if the deposits or withdrawals are disrupted, the balance changes.”

In productive forests, such as tropical forests growing on rich soils, the rates of both “deposits” (tree births) and “withdrawals” (tree deaths) are high. But if tree births suddenly stopped, or if tree death rates doubled, the numbers of trees in these forests would be halved in just 30 years. In contrast, said Stephenson, in less productive forests, such as coniferous forests growing at high latitudes, the same changes could take more than a century to occur.

Another implication of the study is that environmental changes considered beneficial to forests may bring about unexpected forest changes. “Most attention so far has been given to things that stress forests, like increased drought,” said USGS scientist Phil van Mantgem, the study’s co-author. “Less attention has been given to the consequences of changes that can increase forest vigor or productivity, like increased rainfall.”

Environmental changes that increase productivity of a given forest could lead to more rapid turnover of trees, decreasing the average age of trees. In the long run, such changes might affect wildlife populations that prefer younger or older forests, said van Mantgem.

Stephenson and van Mantgem pointed out that increased dominance by younger trees could also lead to changes in the amount of carbon stored in forests, though the direction and magnitude of such potential changes are currently unknown and require more research. Atmospheric carbon dioxide, a heat-trapping gas implicated in climatic warming, increases as carbon storage in forests decreases, and decreases as carbon storage in forests increases. Information regarding such potential changes is therefore needed to reduce uncertainties in predicting future climatic changes.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.usgs.govAll latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

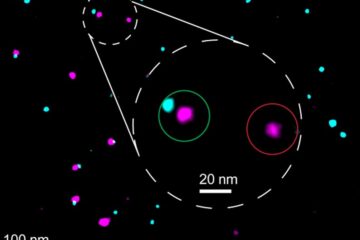

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…