China's Three Gorges Dam Provides New Opportunities for Farmers, Merchants

The level of water in the reservoir behind the dam will top off at 575 feet above sea level during the coming winter. The reservoir pool, covering abandoned cities, houses and farm fields formerly populated by an estimated 1.5 million people, will extend over 400 square miles – equivalent to the land area of Hong Kong. Then by summer the water level will drop 100 feet, and the cycle of flooding and receding water will repeat every year after that.

The region will become home to an entirely new ecosystem as an unprecedented amount of water covers what used to be dry land.

The Three Gorges Dam is the largest hydro-electric project in the world, intended to combine the generation of clean power with downstream flood control, and enable shipping in China’s interior. Critics are concerned that the reservoir will contain factory toxins and raw sewage and that sediment might cause the reservoir level to rise higher than planned, threatening to flood a large city upstream and possibly even send water spilling over the top of the dam.

The flooding is expected to extend as much as 185 miles upstream. Almost 14,000 acres of land in the Pengxi River valley will be seasonally flooded, possibly for as long as six months each year, by the pooling behind the dam.

Opportunities exist to try to make the best of the new ecosystem conditions of unprecedented fluctuating water levels, says William Mitsch, an environmental and natural resources professor at Ohio State University.

Among the possibilities: introducing new agricultural practices during low water levels, creating terraced ponds and wetlands along the borders of the giant reservoir, and establishing food production businesses that capitalize on the changing water levels.

“Nature is going to see something it’s never seen before. There is no ecosystem that has such an exaggerated change in flooding levels, even the Amazon River in South America. This annual variation in water levels will be unlike any other natural river system in the world. If done properly, ecological engineering can minimize some of the impact,” said Mitsch, also director of the Wilma H. Schiermeier Olentangy River Wetland Research Park at Ohio State.

“We’re saying everyone has to think outside the box.”

Mitsch described these opportunities as the lead author of a letter to the journal Science published Friday (10/24).

The letter, coauthored by colleagues at Ohio State and in China, responds to an Aug. 1 Science article exploring the dam’s potential environmental effects, especially on aquatic life in and around the Yangtze River.

Mitsch said farmers planting crops in the reservoir region will need to adjust, or ideally eliminate, the use of fertilizers during growing periods. Fertilizers would leave behind undesired nutrients that would promote the development of algae once standing water covers the crop fields.

“Fertilizers actually won’t be needed,” Mitsch said, because the sediment left behind by flooding will be rich in certain nutrients, especially phosphorus, which is beneficial to many kinds of crops.

Land users also could consider constructing cascading terraced ponds and wetlands along the border of the reservoir to retain water as it recedes and to reduce the loss of nutrients to the pulsing river system.

Perhaps the most commercially viable option would be expansive fish net systems that could be placed to capture fish at the end of the flooding season, as water levels diminish.

Though the original article explored the dam’s possible harm to fish and mammals, Mitsch’s letter noted that mudflats at or near the river system in the summer may provide ideal habitat for shorebirds and other wading birds.

Mitsch, a proponent of the preservation of wetlands around the world, says it’s really too early to tell whether the reservoir behind the dam will function in typical wetland fashion. Often called the “kidneys” of the environment, wetlands act as buffer zones between land and waterways. They filter out chemicals in water that runs off from farm fields, roads, parking lots and other surfaces and hold onto them for years, and also absorb and store carbon.

“It will be a large expanse of water, but for now we just know it will present an ecologically interesting situation,” Mitsch said. “More interesting will be to see how people adapt to it.”

Coauthors of the letter are Jianjian Lu and Wenshan He of Chongxi Wetland Research Centre at East China Normal University in Shanghai; Xingzhong Yuan of Chongqing University; and Li Zhang of the Wilma Schiermeier Olentangy Wetland Research Park at Ohio State.

Contact: William Mitsch, (614) 292-9774; Mitsch.1@osu.edu (Mitsch is traveling in late October, and is best reached via e-mail through Nov. 4.)

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.osu.eduAll latest news from the category: Agricultural and Forestry Science

Newest articles

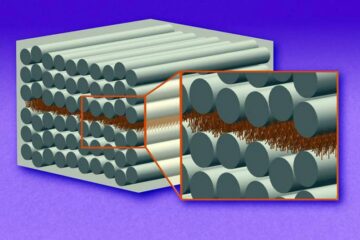

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…

Trash to treasure

Researchers turn metal waste into catalyst for hydrogen. Scientists have found a way to transform metal waste into a highly efficient catalyst to make hydrogen from water, a discovery that…

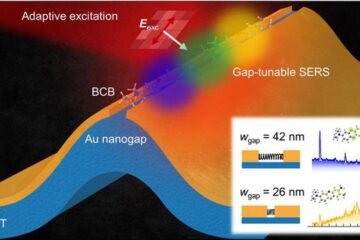

Real-time detection of infectious disease viruses

… by searching for molecular fingerprinting. A research team consisting of Professor Kyoung-Duck Park and Taeyoung Moon and Huitae Joo, PhD candidates, from the Department of Physics at Pohang University…