Materials: Cubic cluster chills out

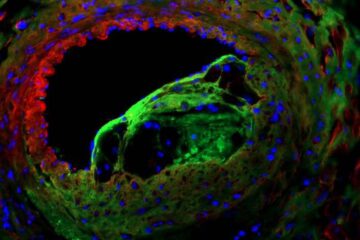

The magnetic refrigerant contains a cubic structure made of two gadolinium ions (pink), two nickel ions (green) and four oxygen atoms (red), surrounded by 2-(hydroxymethyl)pyridine molecules. Copyright : 2014 A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering

Magnetic refrigeration is attracting attention as an efficient way to chill sensitive scientific instruments. This refrigeration method exploits the magnetocaloric effect, in which an external magnetic field controls the temperature of a magnetic material.

Effective magnetic refrigerants are often difficult to prepare, but now Andy Hor of the A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering and the National University of Singapore and his colleagues have created a powerful magnetic refrigerant that is easy to make in the lab [1].

Compounds with a large magnetocaloric effect typically contain atoms with many unpaired electrons, each of which generates its own tiny magnetic moment. During magnetic refrigeration, an external magnetic field forces these atomic magnetic moments to line up in the same direction. As the magnetism of the atoms becomes more ordered (which reduces the entropy of the system), the material’s temperature rises.

Once the heat has been removed by a flowing liquid or gas, the external magnetic field is reduced. This allows the atomic magnetic moments to become disordered again, cooling the material so that it can be used to draw heat from an instrument, before repeating the cycle.

Magnetic refrigerants commonly use the gadolinium(III) ion (Gd3+), because it has seven unpaired electrons. Most gadolinium complexes are made under harsh conditions or take a very long time to form, which limits their wider application. In contrast, the magnetic refrigerant developed by Hor and colleagues is remarkably easy to make.

The researchers simply mixed gadolinium acetate, nickel acetate and an organic molecule called 2-(hydroxymethyl)pyridine in an organic solvent at room temperature. After 12 hours, these chemicals had assembled themselves into an aggregate containing a cube-like structure of atoms at its heart (see image).

The team measured how an external magnetic field affected this ‘cubane’ material as the temperature dropped. Below about 50 K, they found that the material’s magnetization increased sharply, suggesting that it could be an effective magnetic refrigerant below this temperature.

The scientists then tested the effects of varying the external magnetic field at very low temperatures. They found that at 4.5 K, a large external field caused an entropy change that was close to the theoretical maximum for the system — and larger than most other magnetic refrigerants under similar conditions.

According to the team, the magnetocaloric effect of magnetic refrigerants has typically been enhanced by creating ever-larger clusters of metal atoms. In contrast, their cubane shows that much simpler aggregates, prepared under straightforward conditions, are promising as magnetic refrigerants.

Reference

1. Wang, P., Shannigrahi, S., Yakovlev, N. L., and Hor, T. S. A. Facile self-assembly of intermetallic [Ni2Gd2] cubane aggregate for magnetic refrigeration. Chemistry – An Asian Journal 8, 2943–2946 (2013).

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Materials Sciences

Materials management deals with the research, development, manufacturing and processing of raw and industrial materials. Key aspects here are biological and medical issues, which play an increasingly important role in this field.

innovations-report offers in-depth articles related to the development and application of materials and the structure and properties of new materials.

Newest articles

Solving the riddle of the sphingolipids in coronary artery disease

Weill Cornell Medicine investigators have uncovered a way to unleash in blood vessels the protective effects of a type of fat-related molecule known as a sphingolipid, suggesting a promising new…

Rocks with the oldest evidence yet of Earth’s magnetic field

The 3.7 billion-year-old rocks may extend the magnetic field’s age by 200 million years. Geologists at MIT and Oxford University have uncovered ancient rocks in Greenland that bear the oldest…

Decisive breakthrough for battery production

Storing and utilising energy with innovative sulphur-based cathodes. HU research team develops foundations for sustainable battery technology Electric vehicles and portable electronic devices such as laptops and mobile phones are…