Relaxation helps pack DNA into a virus

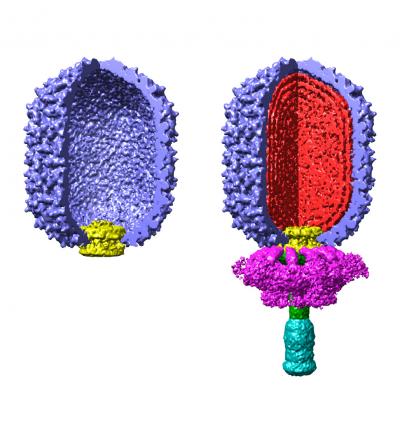

This image shows cross-sections of the empty prohead of the bacteriophage phi29 (left) and the fully assembled virus (right). A molecular motor transports the DNA (red) into the prohead through a portal. Higher resolution TIFF image available. Credit: Jingua Tang and Timothy Baker, University of California, San Diego

DNA is a long, unwieldy molecule that tends to repel itself because it is negatively charged, yet it can spool tightly. Within the heads of viruses, DNA can be packed to near crystalline densities, crammed in by a molecular motor.

“These are among the most powerful molecular motors we know of,” says Douglas Smith, a professor of physics whose group studies them.

Within an infected cell, viruses assemble in a matter of minutes. Smith's group studies the process by isolating components of this system to watch single molecules in action.

They attach the empty head of a single virus, along with the molecular motor, to a microscopic bead that can be moved about using a laser. To another bead, they tether a molecule of viral DNA.

“It's like fishing,” Smith says. “We dangle a DNA molecule in front of the viral motor. If we're lucky, the motor grabs the DNA and starts pulling it in.”

Packaging proceeds in fits and starts, with slips and pauses along the way. These pauses increase, along with forces the motor counters, as the viral head becomes full.

Scientists who model this process have had to make assumptions about the state of the DNA within. An open question is whether the DNA is in its lowest energy state, that is at equilibrium, or in a disordered configuration.

“In confinement, it could be forming all kinds of knots and tangles,” said Zachary Berndsen, a graduate student in biochemistry who works with Smith and is the lead author of the PNAS paper.

To figure this out, Berndsen stalled the motor by depriving it of chemical energy, and found that packaging rates picked up when the motor restarted. The longer the stall, the greater the acceleration.

DNA takes more than 10 minutes to fully relax inside the confines of a viral head where there's little wiggle room, the team found. That's 60,000 times as long as it takes unconfined DNA to relax.

“How fast this virus packages DNA is determined by physics more than chemistry,” Smith said.

DNA's tendency to repel itself due to its negative charge may actually facilitate the relaxation. In related experiments, the researchers added spermidine, a positively charged molecule that causes DNA in solution to spool up.

“You might think the stickiness would enhance packing, but we find that the opposite is true,” said Nicholas Keller, the lead author of this second report, published in Physical Review Letters.

Countering the negative charges, particularly to the point of making the DNA attractive to itself, actually hindered the packaging of DNA.

“The DNA can get trapped into conformations that just stop the motor,” Keller said.

“We tend to think of DNA for its information content, but living systems must also accommodate the physical properties of such a long molecule,” Berndsen said. “Viruses and cells have to deal with the forces involved.”

Beyond a clearer understanding of how viruses operate, the approach offers a natural system that is a model for understanding and studying the physics of long polymers like DNA in confined spaces. The insights could also inform biotechnologies that enclose long polymers within minuscule channels and spheres in nanscale devices.

Shelley Grimes and Paul Jardine, microbiologists at the University of Minnesota co-authored both papers. Damian delToro, a graduate student in physics at UC San Diego, co-authored the paper published by Physical Review Letters.

The National Science Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded the work.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.ucsd.eduAll latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

Silicon Carbide Innovation Alliance to drive industrial-scale semiconductor work

Known for its ability to withstand extreme environments and high voltages, silicon carbide (SiC) is a semiconducting material made up of silicon and carbon atoms arranged into crystals that is…

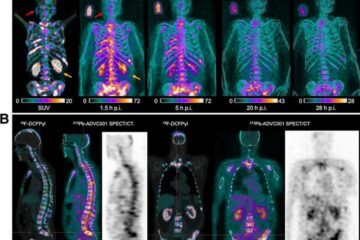

New SPECT/CT technique shows impressive biomarker identification

…offers increased access for prostate cancer patients. A novel SPECT/CT acquisition method can accurately detect radiopharmaceutical biodistribution in a convenient manner for prostate cancer patients, opening the door for more…

How 3D printers can give robots a soft touch

Soft skin coverings and touch sensors have emerged as a promising feature for robots that are both safer and more intuitive for human interaction, but they are expensive and difficult…