Metal nanoparticles shine with customizable color

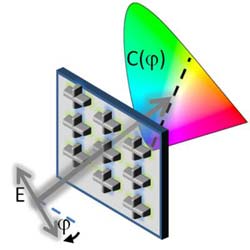

The color output of a new type of optical filter created at Harvard depends on the polarization of the incoming light. Credit: Image courtesy of Tal Ellenbogen.<br>

Engineers at Harvard have demonstrated a new kind of tunable color filter that uses optical nanoantennas to obtain precise control of color output.

Whereas a conventional color filter can only produce one fixed color, a single active filter under exposure to different types of light can produce a range of colors.

The advance has the potential for application in televisions and biological imaging, and could even be used to create invisible security tags to mark currency. The findings appear in the February issue of Nano Letters.

Kenneth Crozier, Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), and colleagues have engineered the size and shape of metal nanoparticles so that the color they appear strongly depends on the polarization of the light illuminating them. The nanoparticles can be regarded as antennas—similar to antennas used for wireless communications—but much smaller in scale and operating at visible frequencies.

“With the advances in nanotechnology, we can precisely control the shape of the optical nanoantennas, so we can tune them to react differently with light of different colors and different polarizations,” said co-author Tal Ellenbogen, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS. “By doing so, we designed a new sort of controllable color filter.”

Conventional RGB filters used to create color in today's televisions and monitors have one fixed output color (red, green, or blue) and create a broader palette of hues through blending. By contrast, each pixel of the nanoantenna-based filters is dynamic and able to produce different colors when the polarization is changed.

The researchers dubbed these filters “chromatic plasmonic polarizers” as they can create a pixel with a uniform color or complex patterns with colors varying as a function of position.

To demonstrate the technology's capabilities, the acronym LSP (short for localized surface plasmon) was created. With unpolarized light or with light which is polarized at 45 degrees, the letters are invisible (gray on gray). In polarized light at 90 degrees, the letters appear vibrant yellow with a blue background, and at 0 degrees the color scheme is reversed. By rotating the polarization of the incident light, the letters then change color, moving from yellow to blue.

“What is somewhat unusual about this work is that we have a color filter with a response that depends on polarization,” says Crozier.

The researchers envision several kinds of applications: using the color functionality to present different colors in a display or camera, showing polarization effects in tissue for biomedical imaging, and integrating the technology into labels or paper to generate security tags that could mark money and other objects.

Seeing the color effects from current fabricated samples requires magnification, but large-scale nanoprinting techniques could be used to generate samples big enough to be seen with the naked eye. To build a television, for example, using the nanoantennas would require a great deal of advanced engineering, but Crozier and Ellenbogen say it is absolutely feasible.

Crozier credits the latest advance, in part, to taking a biological approach to the problem of color generation. Ellenbogen, who is, ironically, colorblind, had previously studied computational models of the visual cortex and brought such knowledge to the lab.

“The chromatic plasmonic polarizers combine two structures, each with a different spectral response, and the human eye can see the mixing of these two spectral responses as color,” said Crozier.

“We would normally ask what is the response in terms of the spectrum, rather than what is the response in terms of the eye,” added Ellenbogen.

The researchers have filed a provisional patent for their work.

Kwanyong Seo, a postdoctoral fellow in electrical engineering at SEAS, also contributed to the research. The work was supported by the Center for Excitonics, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, and Office of Basic Energy Sciences; and Zena Technologies. In addition, the research team acknowledges the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard for fabrication work.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.seas.harvard.eduAll latest news from the category: Power and Electrical Engineering

This topic covers issues related to energy generation, conversion, transportation and consumption and how the industry is addressing the challenge of energy efficiency in general.

innovations-report provides in-depth and informative reports and articles on subjects ranging from wind energy, fuel cell technology, solar energy, geothermal energy, petroleum, gas, nuclear engineering, alternative energy and energy efficiency to fusion, hydrogen and superconductor technologies.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

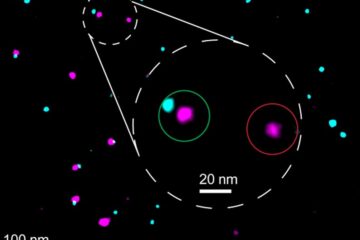

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…