Hopping Protons

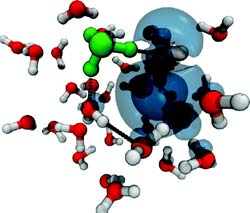

Snapshot from ab Initio Molecular Dynamic Simulation. © Schmidt

How do you simulate the behaviour of protons and amino acids on the computer? How do you depict experiments to study their behaviour as more or less water is introduced? These questions may seem trivial in this age of powerful computers. Yet, it turns out this task will remain almost impossible to solve until new mathematical algorithms are found. Protons simply behave too quickly and too “unpredictably”.

In the DFG Research Centre MATHEON project “Modelling and optimizing functional molecules“, Dr. Burkhard Schmidt is working on this problem under the direction of Prof. Christof Schütte. He is using computer simulations to investigate the role of water as a solvent when it is added to amino acids or peptides in tiny steps. His main objective is to research the proton transfer between two end-groups – which leads to the formation of so-called zwitterions – and the proton transfer between appropriate side chains – which leads to the formation of so-called salt bridges.

Schmidt’s work is still at the fundamental research level, but his results will be of enormous significance to many fields. Proton transfer plays a role in energy conversion within solar cells and fuel cells, for example, and applies to the energy flow in batteries. It is even relevant to the development of new drugs.

A zwitterion is a molecule that has two or more functional groups, where one group is positively charged and another negatively charged. The molecule is therefore electrically neutral overall. Amino acids are natively electrically neutral molecules. If you dissolve them in water, however, the water protons start to ‘hop’, causing one end of the amino acid to become negatively charged and the other end to become positively charged. The protons involved in this process remain constantly in motion, forever forming new bonds. If protons hop all the way along neighbouring molecules, then charges can also be transported over nanometre-scale distances in so-called water bridges or “water wires”. All this happens on extremely short time scales.

Dr. Schmidt believes his project will help understand proton transfer mechanisms on a microscopic level. He is currently focusing on amino acids and small peptide chains. The researcher describes his approach: “Although the vast majority of biological processes occur in watery solution, our studies start by looking at isolated amino acids and peptides, in order to distinguish intramolecular from intermolecular processes. Then we gradually add individual water molecules to our simulations. That way, we can study the influence of the solvent in a controlled manner.” It is an ambitious project, since such studies can only be performed in computer simulations, and would be monumentally difficult or simply impossible as real experiments.

The scientist intends to explain, for example, how many water molecules are required to make amino acids or peptides change from neutral to zwitterionic form. He also intends to study what happens to a salt bridge as water molecules are added. “Furthermore, it is interesting to simulate these processes in their time-dependency, to be able to study the timescales of the investigated processes as well. Essential questions include how fast protons can be released from or deposited onto the appropriate side chains, or on what timescale protons are transferred between protein and water, and how fast protein transport is along water bridges,” Burkhard Schmidt explains.

In his studies, Schmidt will employ methods to calculate the energies or forces from the electron structure at every time step of the simulation. This distinguishes his work from “conventional” computer simulations, in which empirical models are applied to calculate energies and forces between the atoms. “Aside from the questionable accuracy and applicability of such empirical models, their fundamental limit is that they cannot describe the breaking and forming of chemical bonds. I’m not satisfied with that,” he says. His current research builds upon a previous project in which Dr. Schmidt studied the reaction of a proton and an electron in a water cluster. (Cluster=microdroplet)

Thanks to his mathematical/physical methods, Burkhard Schmidt is already able to calculate chemical processes a number of picoseconds long (1 picosecond = 0.000 000 000 001 second) on mainframe computers. “That’s a lot already, but I would like to reach up to nanoseconds (0.000 000 001 second),” the scientist concludes.

More information:

Dr. Burkhard Schmidt,

phone: +49 30 838 75369,

Email: burkhard.schmidt@fu-berlin.de

Media Contact

All latest news from the category: Life Sciences and Chemistry

Articles and reports from the Life Sciences and chemistry area deal with applied and basic research into modern biology, chemistry and human medicine.

Valuable information can be found on a range of life sciences fields including bacteriology, biochemistry, bionics, bioinformatics, biophysics, biotechnology, genetics, geobotany, human biology, marine biology, microbiology, molecular biology, cellular biology, zoology, bioinorganic chemistry, microchemistry and environmental chemistry.

Newest articles

High-energy-density aqueous battery based on halogen multi-electron transfer

Traditional non-aqueous lithium-ion batteries have a high energy density, but their safety is compromised due to the flammable organic electrolytes they utilize. Aqueous batteries use water as the solvent for…

First-ever combined heart pump and pig kidney transplant

…gives new hope to patient with terminal illness. Surgeons at NYU Langone Health performed the first-ever combined mechanical heart pump and gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery in a 54-year-old woman…

Biophysics: Testing how well biomarkers work

LMU researchers have developed a method to determine how reliably target proteins can be labeled using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. Modern microscopy techniques make it possible to examine the inner workings…