Freshwater fish at the top of the food chain evolve more slowly

For avid fishermen and anglers, the largemouth bass is a favorite freshwater fish with an appetite for minnows.

A new study finds that once they evolved to eat other fish, largemouth bass and fellow fish-feeders have remained relatively unchanged compared with their insect- and snail-eating cousins. As these fishes became top predators in aquatic ecosystems, natural selection put the breaks on evolution, say researchers.

A highly sought-after game fish, the largemouth bass belongs to a group of roughly 30 freshwater fishes known as centrarchids. Centrarchids are native to North America but have since been introduced into lakes, rivers and streams worldwide. This group of fishes eats a wide range of aquatic animals, says first author David Collar. “There's a good deal of diet diversity in the group,” says Collar, a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University. “Some species feed on insects, snails, or small crustaceans, and others feed primarily on fish.”

In terms of nutritional value, fish are loaded with fats and proteins needed for growth, explain the researchers. “Fish make great fish food,” says co-author Brian O'Meara of the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center. “But they're hard to catch,” says O'Meara.

Biologists have long known that certain head and body shapes make some centrarchids better at catching fish than others. To catch, kill, and swallow fish prey, it helps to have a supersized mouth. “There are a lot of different sizes and shapes that will be fairly good at feeding on insects,” Collar explains. “But there's really only one way to be good at feeding on fish – you need a large mouth that can engulf the prey.” The largemouth bass is a prime example: “There's no fish out there that's a better fish-feeder,” says co-author Peter Wainwright of the University of California at Davis.

One key to feeding on fish is to have a large mouth, but the other part of the equation is speed, the researchers explain. “A largemouth bass mostly relies on swimming to overtake its prey, and at the last moment will pop open its mouth — kind of like popping open an umbrella — and inhale the prey item,” says Wainwright. “They're able to strike very quickly and inhale a huge volume of water, which allows them to catch these big elusive prey.”

For largemouth bass and other species that feed primarily on fish, the researchers wanted to know how this feeding strategy affected the pace and shape of evolution. “The question we wanted to ask was: What is the interplay between the evolution of diet and the evolution of form?” says Collar.

To find out, the researchers examined museum specimens representing 29 species of centrarchid fishes. Using a chemical process to stain and visualize the bones, muscles, and connective tissue, they measured the fine parts of the head and mouth. “A fish mouth is much more complicated than our own mouth,” says Wainwright. “Whereas we have one bone that moves — our jaw — fish actually have two dozen separately moving bones, and lots of muscles that move those bones in a coordinated fashion.”

By mapping these measurements onto the centrarchid family tree — together with data on what each fish eats — the researchers were able to reconstruct how diet and head shape have changed over time. “It looks as if the variety of head shapes and sizes in centrarchids is strongly influenced by what they eat — primarily whether they eat other fish or not,” says Collar.

More importantly, when they compared fish-feeders with species that eat other types of prey, the researchers found that bass and other centrarchids that feed primarily on fish have remained relatively unchanged over time. Once they evolved the optimal size and shape for catching fish — roughly 20 million years ago — natural selection seems to have kept them in an evolutionary holding pattern, the researchers say.

“At some point in the history of this group, some of them started feeding on fish,” says Wainwright. “And once they achieved a morphology that was good at feeding on fish, they tended not to evolve away from that,” he adds. “They were already good at catching the best thing out there. Why should they diversify any more? Life was good.”

The team's findings were published in the June 2009 issue of Evolution.

CITATION: Collar, D., B. O'Meara, P. Wainwright, and T. Near. (2009). “Piscivory limits diversification of feeding morphology in centrarchid fishes.” Evolution 63(6): 1557-1573.

The National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent) is an NSF-funded collaborative research center operated by Duke University, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and North Carolina State University.

Media Contact

More Information:

http://www.nescent.orgAll latest news from the category: Studies and Analyses

innovations-report maintains a wealth of in-depth studies and analyses from a variety of subject areas including business and finance, medicine and pharmacology, ecology and the environment, energy, communications and media, transportation, work, family and leisure.

Newest articles

Optimising inventory management

Crateflow enables accurate AI-based demand forecasts. A key challenge for companies is to control overstock and understock while developing a supply chain that is resilient to disruptions. To address this,…

Cause of rare congenital lung malformations

Gene mutations in the RAS-MAPK signaling pathway disrupt lung development in the womb. Most rare diseases are congenital – including CPAM (congenital pulmonary airway malformations). These are airway malformations of…

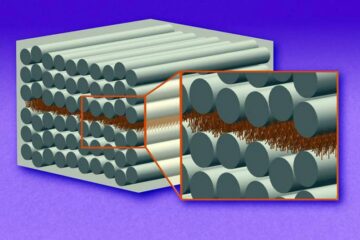

“Nanostitches” enable lighter and tougher composite materials

In research that may lead to next-generation airplanes and spacecraft, MIT engineers used carbon nanotubes to prevent cracking in multilayered composites. To save on fuel and reduce aircraft emissions, engineers…